How to Write a History Book

May 10th, 2018 - By Patrick T. McBriarty

Each author has her or his own approach, but the trick to writing a book is trusting the process. As Hemingway advised a young writer, “the first draft of anything is shit!” explaining that the real work comes in the revising, rewriting, and reworking of a manuscript as many as forty, maybe fifty times, to get to the finished product.

For many writers, myself included, the first draft can be the hardest to complete, even though it is rarely where the bulk of the time lies. It is difficult because it means turning off one’s internal editor, eschewing expectations, and silencing your ego to get something, anything, however bad, on the page. Trying to make it good, let alone great, out of the gate is neigh impossible and just slows or can kill the process before it even begins. The desire for perfection at the onset just causes procrastination or at worst writer’s block.

A few years ago, I received great advice (thanks Motsey!) from a fourth-grade class sharing the concept of a first draft as a “sloppy copy.” Thinking of it in this way – that the initial draft does not matter – helps take the pressure off and encourages free writing. No expectations. Just write. The first baby step in the process. Of course, it is not your best work. That IS the point! Get some ideas on paper (or into the computer). Calling it a sloppy copy reminds you not to worry how it looks, because later you will of course edit and fix it up.

A few years ago, I received great advice (thanks Motsey!) from a fourth-grade class sharing the concept of a first draft as a “sloppy copy.” Thinking of it in this way – that the initial draft does not matter – helps take the pressure off and encourages free writing. No expectations. Just write. The first baby step in the process. Of course, it is not your best work. That IS the point! Get some ideas on paper (or into the computer). Calling it a sloppy copy reminds you not to worry how it looks, because later you will of course edit and fix it up.

Though my friends may beg to differ, I do not really consider myself creative. So my process leans heavily on research, often gathered over the course of several years, regularly immersing myself for days, weeks, and ideally, months at a time in original sources, secondary books, and related topics to develop a story. Intensive immersion gets much of the material in your head to encourage long jags of writing (and editing) so the words and ideas can flow and pour out. This is ideal when there are little or no interruptions externally, or internally – like feeling the need to look things up or fumbling with gaps in the story. In early drafts one trick I use to minimize internal interruptions is to quickly identify a gap and move on. I do this by simply acknowledging to myself, “I don’t know this part,” and make a note in the text like, [check this], [look this up], or [source?] to leave it behind and keep on with the flow of writing. By making these notes in bold and brackets they are easy to pick off and deal with later during an edit review.

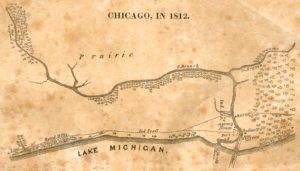

Of late I have been collecting original documents surrounding Chicago on the cusp of the War of 1812 (which lasted until 1816). I have come to trust in the process of developing a collection, which was how I approached my first book on Chicago’s bridges. Collecting itself prompts additional queries and research needed to fill in gaps and offers, for me at least, what becomes a very powerful launching pad of expertise. The best way to share this hard-won knowledge broadly is to then write about it. The writing process forces me to ruminate and distill the collection into something palatable and make it accessible to share with others. In this manner the context, themes, and hooks to a story arise from the previously disparate parts into a greater more concise whole. Less is more. Through the work the gems are revealed and develop into a rich, engaging story without dragging the listener (or reader) through the digging, dreck, and tailings of mining a story.

Of late I have been collecting original documents surrounding Chicago on the cusp of the War of 1812 (which lasted until 1816). I have come to trust in the process of developing a collection, which was how I approached my first book on Chicago’s bridges. Collecting itself prompts additional queries and research needed to fill in gaps and offers, for me at least, what becomes a very powerful launching pad of expertise. The best way to share this hard-won knowledge broadly is to then write about it. The writing process forces me to ruminate and distill the collection into something palatable and make it accessible to share with others. In this manner the context, themes, and hooks to a story arise from the previously disparate parts into a greater more concise whole. Less is more. Through the work the gems are revealed and develop into a rich, engaging story without dragging the listener (or reader) through the digging, dreck, and tailings of mining a story.

My process invariably involves going to relevant institutions and libraries, however more and more initiating a project occurs via online sources. Research here, is invariably incomplete, but can usually provide the framework and the discovery of key and unexpected resources or institutions leading to new source documents, books, or journals (that are not online) critical to reach the heart of a project. Like making sausage it gets very messy before anything is cleaned up and readied for sale.

My process invariably involves going to relevant institutions and libraries, however more and more initiating a project occurs via online sources. Research here, is invariably incomplete, but can usually provide the framework and the discovery of key and unexpected resources or institutions leading to new source documents, books, or journals (that are not online) critical to reach the heart of a project. Like making sausage it gets very messy before anything is cleaned up and readied for sale.

Finding or choosing a story can be a topic unto itself, but in short, find something that resonates or is fascinating to you. It should be something you want to be associated with and champion. Remember you will be stuck with it a long time, even after the book is finished. Some people fall in and out of love with particular ideas more easily than others, so knowing yourself helps in choosing the “right” topic, idea, or story. Ideally it has many facets for staying power with new avenues to meander keeping and it interesting. I view writing as a process for thinking deeply and means of refining thoughts, concepts, and ideas, so choose something you enjoy and feel strongly about.

In researching a 200-year old scalping, murder, and massacre the best original sources are letters written at the time and eye-witnesses accounts, ideally written just after the event, but frequently from recollections decades later. Back then a few institutions (like the Indian Department or War Department) and some military leaders kept letter books of inbound and outbound correspondence. Additionally, the papers and correspondence of famous and wealthy individuals are usually passed on and preserved, but many key documents are subject to the whims of time. An untimely death, a fire, or unknowing heirs can lead to the inadvertent destruction of many potentially historic papers. Occasionally, previous historians (like say Lyman C. Draper or Clarence M. Burton) traveled, collected, interviewed, and gathered many stray bits to create wonderful and invaluable historic collections.

In researching a 200-year old scalping, murder, and massacre the best original sources are letters written at the time and eye-witnesses accounts, ideally written just after the event, but frequently from recollections decades later. Back then a few institutions (like the Indian Department or War Department) and some military leaders kept letter books of inbound and outbound correspondence. Additionally, the papers and correspondence of famous and wealthy individuals are usually passed on and preserved, but many key documents are subject to the whims of time. An untimely death, a fire, or unknowing heirs can lead to the inadvertent destruction of many potentially historic papers. Occasionally, previous historians (like say Lyman C. Draper or Clarence M. Burton) traveled, collected, interviewed, and gathered many stray bits to create wonderful and invaluable historic collections.

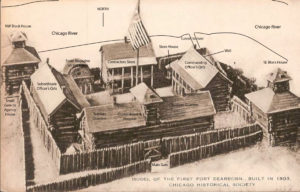

For my current project, of the approximately one-hundred whites in Chicago in 1812, most were killed or died in captivity after the Battle of Fort Dearborn. The incident occurred on August 15, 1812, on Chicago’s lakefront. The Indians looted the abandoned fort and burned it down the next day. Unfortunately, very little Native American perspective on events in Chicago were recorded due to oral traditions (i.e. no recorded history) and aggravated relations of the times. Few white survivors had the luxury of carrying documents and very few made it back to civilization. Thus, primary accounts are rare and correspondence to individuals outside of Indian Country (as the young United States called much of the new Territories) are the next best source.

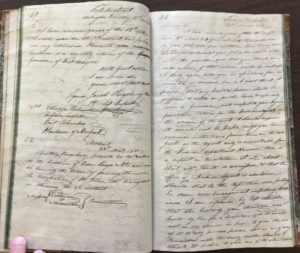

The additional wrinkle is all these correspondence in that era was hand written. A commercially successful typewriter would not be invented until 1868. Although many documents were previously transcribed and can be found online, in books, or historic collections, but rarely all in one place. The labor-intensive work of research comes in visiting places like the National Archives in Washington, D.C., the Detroit Public Library, Chicago History Museum’s Research Center, the Newberry Library, Wisconsin Historical Society or various college libraries such as Indiana University or the University of Chicago. There items are located and discovered, and I use my phone to quickly photograph documents for later review. These are deciphered and many are transcribed, some painstakingly so, depending on the handwriting and quality of the document. Additional trips to these institutions usually follow after the initial material is digested to gather missed documents, correct blurry images, or pursue new leads. Frequently documents are only on microfilm, often created from copies of copies, making the collection and transcription even more time consuming. Needless to say, research can be quite tedious in the quest for hidden gems that may not exist, but the result teases out additional background about the social landscape, customs, and behavior of the era a few puzzle pieces at a time.

The additional wrinkle is all these correspondence in that era was hand written. A commercially successful typewriter would not be invented until 1868. Although many documents were previously transcribed and can be found online, in books, or historic collections, but rarely all in one place. The labor-intensive work of research comes in visiting places like the National Archives in Washington, D.C., the Detroit Public Library, Chicago History Museum’s Research Center, the Newberry Library, Wisconsin Historical Society or various college libraries such as Indiana University or the University of Chicago. There items are located and discovered, and I use my phone to quickly photograph documents for later review. These are deciphered and many are transcribed, some painstakingly so, depending on the handwriting and quality of the document. Additional trips to these institutions usually follow after the initial material is digested to gather missed documents, correct blurry images, or pursue new leads. Frequently documents are only on microfilm, often created from copies of copies, making the collection and transcription even more time consuming. Needless to say, research can be quite tedious in the quest for hidden gems that may not exist, but the result teases out additional background about the social landscape, customs, and behavior of the era a few puzzle pieces at a time.

The thrill of the hunt and fact very few people are willing and lack the time or patience to do exhaustive research keeps me going – along with a dogged curiosity and focus. Compounding the “fun” of history is the shift in use of the English language requiring an understanding of cryptic no-longer used phrasing, unexplained contextual inferences, and old word connotations. People of the early-1800s placed great importance on personal reputation and propriety so letters are rarely direct or plain spoken. Thus, the struggle is to quickly identify unsaid meanings and inferences that were quite clear in their day. The juicy bits of inferred nuances, alarm, scandal, indignity, or impropriety help create a good story.

Detective work also pieces together social networks, relationships, and alliances of the cast of characters and supporting players to better interpret a collection. Thankfully by 1812, most of the movers and shakers did read and write. They interacted, traveled widely, and corresponded with military officers, government officials, family, and friends elsewhere. Finding the resulting documents may uncover items that have never before been published. And a methodical approach almost invariably results in the discovery of a new, untold history. As the research winds down, the real work of writing begins to sort and piece together the collection into your own words. In telling and retelling the story the ideas emerge and become refined to be consumed by an audience, so I also find it very helpful to talk about a project well before it is finished. That is how (my) history books are created.